Behind The Scenes - Working Criteria

How do you begin?

It starts with looking. Regardless of what I’m doing or where I am. Being aware of what is going on, observing the world around me. Noting shapes, colours, light and shade, structure. Things that attract my visual attention. I keep a notebook with me usually and a camera.

What about ideas?

I used to be an illustrator and as such my work was about adding clarity and information to expand on a given text. To do this you need to be able to define an idea or concept which will add more to the perception of the text rather than just describing in visual forms what the author is saying. In essence you become a problem solver.

When I reached an age and state where I no longer wanted to work entirely at the behest of other people, I started by applying the same criteria to myself. I became my own client. It was hard defining what I wanted to say. I was living in a completely different environment, small town in Devon as opposed to west London and I was bombarded by the differences. The landscape of course but I have always been interested in people and this is my preferred subject matter. As an illustrator most of my work revolved around the depiction of people and animals, historically and in the present day for fiction and non fiction. It seemed natural then to transfer this interest to my new surroundings.

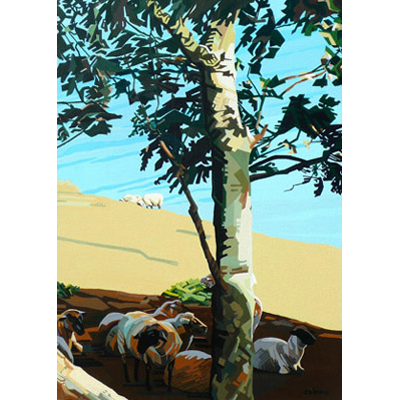

I didn’t know many people and it was not easy finding models and workspace, so I took myself outside and started to explore the locale and, discovered sheep. No they don’t keep still while you try to draw them, but if you can fool them into ignoring you (they are both skittish and inquisitive) and you start to look, their stance, character, interaction with others and in the landscape, breeding variations in shape and colour, the way they look at you, became a wonderful subject matter.

So you started painting sheep?

Yes, well drawing actually. Out at Stoke Fleming which is about 3 miles from Dartmouth where I live, there are a set of fields on the high cliffs with the sea below. I was there one day watching the newly shorn sheep grazing. As with a lot of south Devon, the hillsides and cliffs are very steep and as a poor walker and townie it seemed amazing to see how well they coped. Four legs help of course. But it was the light, so intense, bouncing off the water with deep pools of shade where the sheep gathered to get out of the heat at midday that really got me started. I drew, took some photographs as backup and came home to work.

Don’t you paint outside?

No. I don’t see well enough any more and besides, years as an illustrator meant that I worked at a desk and this has become a habit. I’m not a fast painter, I use paint tightly in defined areas and this takes time. I don’t like the texture of paint when I’m using it. It has to be smooth, flat almost as though it were printed! I’ll quickly lay colour if roughing something out but prefer to structure the image. Depth within the painting is given by analysis of colour and light, by breaking down the shapes that I see into pattern, it seems to work.

So did you make a series of sheep paintings?

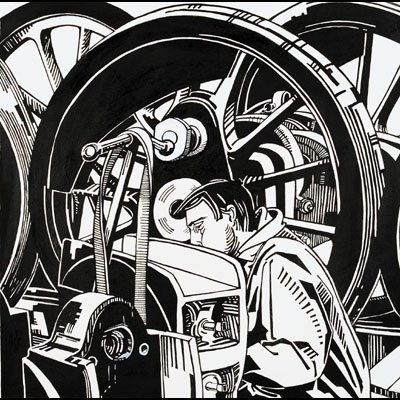

Yes and it’s ongoing though I am now looking at other subjects as well. I seem to work in series. Two that I am still involved in are Working Man

and The Land Around.

Yes, I suppose once you’ve seen one sheep you’ve seen them all.

No way! Well I don’t expect everybody to recognise their charms, but they are really interesting as subject matter. Have you ever looked at the different textures of wool. Some sheep have really thick, dense fleeces others are silky looking with incredible depth of colour. I like to see how they reflect the colours around them so that they sometimes appear blue or green. Their faces too, so different from breed to breed (I particularly like the Blue Faced Leicester, they have wonderfully patrician noses).

Are you talking about portraits then?

I suppose so, I think they are a worthy subject, and after all people have had their animals painted for centuries. I’m just following a long tradition.

Can you tell me about the other things you like to paint.

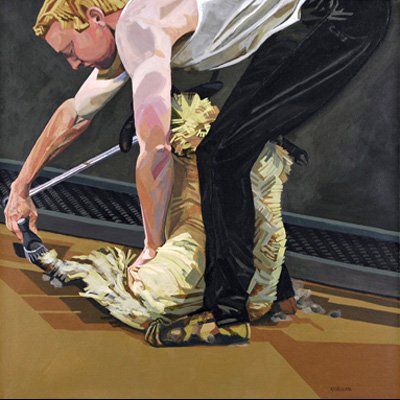

People more than anything. As they do things or are involved in their everyday activities, at work particularly. Again it was the lack of model that shifted me into The Working Man

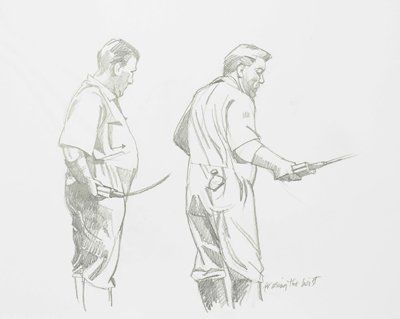

series. I think that I am probably old fashioned and associate working on the human figure with being in the studio and drawing and painting from life. This has not been a possibility and so I have taken myself out to where I can watch people working and draw and photograph accordingly.

Your pictures all seem to be of men.

Yes. On the whole the industries I am interested in and which are close enough to where I am based to research, are probably more physical than the things that women become involved in.

Isn’t that rather sexist, a lot of women do physical work?

Maybe it is but I find men’s bodies better to look at! Generally shapes and angles are harder, more defined. That said, the ubiquitous overall can and does cover a multitude of bodies. I am not looking for the perfect male specimen – different ages, shapes, decrepitude even are things I find interesting and can be the start for drawings. One can take political correctness too far! I paint and draw as a necessity, so I please myself. To go back to something I said earlier; I am now, for want of a better word my own client. I don’t choose things or tweak things to pander to someone else’s wishes or requirements. If a subject works for me, that is the start and the end of it. If ultimately, people choose to buy my work, it is because the subject matter and what I have done with it meets a criteria of theirs.

But looking at your list of work, there are items which you have marked up as commissions. If somebody commissions you aren’t they then your client and you have to do what they want?

Yes that’s correct but it is also feels a very different situation to being commissioned as an illustrator. I earned my living as an illustrator for nearly 30 years. I enjoyed it very much and felt privileged to be in a situation where I was paid to do something I loved. Yet, I don’t know any illustrator who, over the years, has not been frustrated by some seemingly inconsequential change that has been requested by the commissioning person.

Now I am sometimes asked to produce a painting or drawing for a person, who may want a particular subject. Presumably they are familiar with my work and are prepared to give me, within certain constraints, a free hand.

When being commercially commissioned for whatever sort of illustration to be published, and this includes film and tv, the editor has an idea usually of the sort of thing that is required, not just content, but style, concept, media to be used, approach - humour, realism, historical accuracy etc. This governs who they choose to use and therefore there are very specific requirements to be met which may ultimately affect the commercial viability of the project. While one can suggest that changes may not in your opinion be valid, the commissioner has a different view, perspective and experience. This is so different to being commissioned to produce a drawing or painting for somebody’s domestic use and pleasure. The commissioner in this instance is approaching the artist to put their abilities to a subject matter close to the commissioners heart and, and this is the key point, they are then prepared, usually to accept the visual decisions that the artist has made.

You say usually.

It happens that sometimes what the artist produces is not what the commissioner envisaged. Examples of this abound through history. What happens is the work can be rejected out of hand, paid for partially or not paid for at all, paid for and then hidden or destroyed. Like anything you do at the behest of someone else, it is a gamble, but it is a gamble where the artist can specify too and that makes it a very different proposition.

You mentioned earlier the Working Man series. Can you tell me a bit more about it.

I live in an area where agriculture and fishing are the two main industries. The quay at Dartmouth is home to crab and lobster fishing boats as well as yachts, pleasure craft and the ferries to the east side of the river Dart. Brixham a small town about 5 miles from Dartmouth across the river, has a larger fishing industry, with a big fish quay and market and a wider range of craft, some of them quite large.

A couple of years ago I got permission to go onto the fish quay and settled down to draw and take photographs. The first thing that hit me was the vibrant colour of the nets. Truly turquoise and mended with red and yellow, green and white. The plastic buckets and the trays that the fish are loaded into are equally vibrant. The boats also are multi coloured and rust too can be amazingly rich. The fishermen, all ages and sizes in old jackets, jumpers and beanies but with rubber (?) dungarees and boots in yellow and red, held up by multi-coloured braces, wearing electric blue rubber gloves. Who could not be knocked out by this feast of colour.

The first time I went, I timed my arrival to be there when the catch was being unloaded. Hoists are used but there is an enormous amount of hard physical work, bending and lifting, shovelling the ice into the crates, driving the fork-lift trucks, clearing up and cleaning the decks. All this provided a wide range of material to explore and develop once back in my workroom. This is how The Working Man

series started. The same approach is applied to any/all working situations.

How do you go about starting a fishing painting for example?

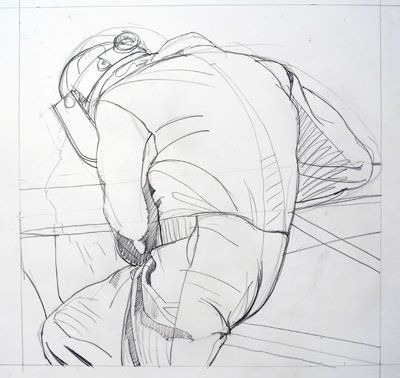

I started off by redoing drawings of the fishermen, using the onsite scribbles as the starting off point. The photographs were great backup. Then I started working on layouts – a hangover from being an illustrator. These can be quite small thumbnails which are framed up to different proportions. I’ll then enlarge these drawings up to the size that I hope to work in. Changing the size can quite radically alter the viability of the design. Size and space changes the dynamic. The drawings are in line, pencil mostly but sometimes ink.

Do you make colour roughs and preliminaries?

No. When I have in the past, and of course I had to as an illustrator, I found that the work lost its spontaneity. So now, I keep colour and treatment ideas in my head and loosely block in colour onto the canvas or paper that I’m working on once the drawing has been transferred to it

and corrected.

and corrected.

What do you mean corrected?

Once happy with the design I will have made a full size drawing and then transferred it to the finished surface either by squaring it up or using trace down which is a form of carbon paper for artists. If you trace something down even from your own accurate drawing, you have moved away from that accuracy, the hand slips, the line becomes woolly and so I find it necessary to correct the drawing so it is as good as it can be. The drawing is just in pencil line, no shading and highlights! Then I’ll go over the line with a soft brush and a neutral colour. Paradoxically, I don’t mind if the accuracy is then lost because the brushwork is looser and softer, I know that the underlying work was right. Colour is very loosely blocked in over the whole image and allowed to dry. It may be an idiosyncrasy of mine, but once the drawing is right I don't mind messing it up by working loosely in colour over it, then, I can reclaim it bit by bit. I don’t mean by starting in the top left hand corner and working down but by taking the whole image up layer by layer. It can be time consuming.

Is this what you do with drawings too, like the ones in the railway workshop?

Mostly, though if the drawing is just in ink, like the railway ones, once the pencil preliminaries are ok I’ll go straight into inking one of the most complex parts. If I can get this to work then I’ll carry on. If it is a disaster then I have to start over again.

Can’t you correct the ink drawing then?

You can’t wash out ink, you can scrape it if the surface you are working on has a substantial china coated surface, but that can scar.

Some of your drawings look like wood block prints, are they?

No. I did a bit of print making when I was a student but decided to go down the graphic design route. I think this shows in my work now and what you call wood block prints is a reflection of the requirements made by graphic design (certainly in the days when I worked

as a designer though perhaps not so much these days).

What are you planning for the future?

More of the same I suppose. I like to have a range of things going on all the time, hence the different series. I can't produce endless versions of the same thing. I need to recognise difficulties that come up or set new challenges for myself so that I can problem solve. It's what I have always done and very satisfying if it works!